The cybersecurity industry’s talent shortage isn't due to a lack of people, but a broken talent pipeline.

Rosie Anderson, the Head of Strategic Solutions at th4ts3cur1ty.company, argues that the automation of junior roles in pursuit of short-term efficiency is creating a future leadership deficit.

Anderson proposes a strategic shift toward reinvesting in human-centric models, mentoring, and hiring for a problem-solving mindset to ensure long-term resilience.

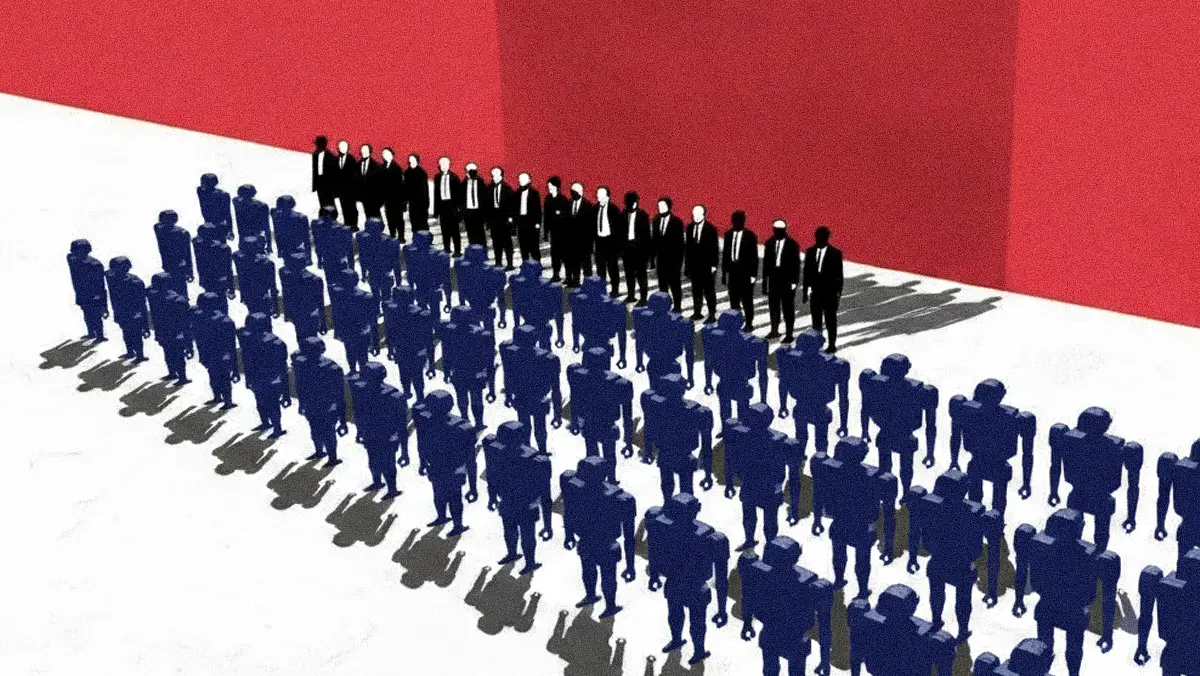

The widely cited cybersecurity “talent shortage” isn’t a scarcity of people. It’s a broken talent pipeline. The pipeline is breaking because many organizations, chasing short-term efficiency, are automating the junior roles that once served as the industry's training ground. Accelerated by AI tools that absorb entry-level work, the automation of these roles is creating a system that risks a future leadership deficit: a problem that surfaces as stalled career progression and high CISO turnover.

Rosie Anderson, Head of Strategic Solutions at th4ts3cur1ty.company, brings a unique perspective to the talent crisis. A prominent community leader who co-founded BSides Lancashire and helped relaunch BSides Leeds, Anderson pivoted into cybersecurity after a 20-year career in tech recruitment. Her unique perspective is informed by years on the front lines of hiring and talent development, including her former role as Head of Industry Mentoring at CAPSLOCK. Recognized as Cyber Newcomer of the Year in 2025 and one of the Most Inspiring Women in Cyber Security in 2024, Anderson says that the industry’s entire conversation around talent is fundamentally flawed.

"There isn’t a shortage of people who want to get into cybersecurity. What we’re creating is a massive pipeline problem by removing the roles where people learn, make mistakes, and build real experience," says Anderson. The long-term cost of automating these foundational roles is the slow decay of practical knowledge. Anderson notes this strategy can become a self-defeating loop.

Operators, not owners: "They're not learning through hands-on experience of breaking and fixing and having that mindset of, 'How does this work?'" Anderson says. "Instead, the mindset is becoming, 'How do I do this? I don't care about how it works because the AI will worry about that.'" The irreplaceable value of human capital is clear. "LLMs, by definition, are not capable of original thought," she states. "That's what people are for."

A gap in understanding: "The next issue is going to be that there's no new junior training data for those LLMs, so that's going to stall the pipeline as well." By removing the human training ground, organizations risk creating a generation of tool operators skilled at performing tasks yet lacking the deeper problem-solving abilities that come from understanding why a system works. She sees this as a cultural challenge with direct business implications: a potential gap between performing a task and truly understanding a system.

The solution, according to Anderson, requires a change in business strategy, beginning with leaders being honest about their end goals. For those building to last, part of the answer lies in reinvesting in a human-centric model that looks beyond the next quarter and asks where future leaders will come from. In practice, this involves recognizing that hiring juniors is an investment in developing a company's next generation of senior talent, who themselves need someone to mentor.

Exit or existence: "A business built to sell will have goals that are different from a business that's stable and wants to be around for the next 100 years," Anderson explains. "What happens when that software fails? If it's only being fed more and more AI, everything's going to become very beige. It can only learn from what it's been fed, so there's no original thought coming into the technology." Anderson says that over-reliance affects both technical resilience and competitive edge.

For Anderson, effective security is ultimately found in people. She recommends hiring individuals who are confident they can find answers to what they don't know. "We need those problem solvers and those fixers and those hackers and breakers who understand how things work because we don't know what's coming down the line." She stresses that the priority is to understand the business as a whole, not just the technology. "How the business works, how the business operates, the people, what the cadence of that business is, what the crown jewels are and how to protect those," and to honestly answer, "Are we protected, or do we at least have a plan if an attack happens tomorrow on our business?"

Anderson concludes with a question that organizations can ask to test their resilience, a question that bypasses talk of tools and budgets to focus on an asset that is often overlooked in a crisis: deep, institutional knowledge held by experienced people. "If we were hit with ransomware and we had to rebuild all of our technology from scratch, who would know how to do it?"