Personal liability after a cyber breach now hinges on insurance fine print, not reporting lines, leaving CISOs exposed to risks they can’t delegate away.

Kurtis Suhs, Founder and CEO of Concierge Cyber and a former FDIC investigator, details how knowledge exclusions, severability clauses, and regulatory rules determine when leaders pay personally.

The strongest defense is proactive risk management backed by documentation, tight insurance language, and verified vendor coverage, creating a clear record of reasonable decisions when scrutiny arrives.

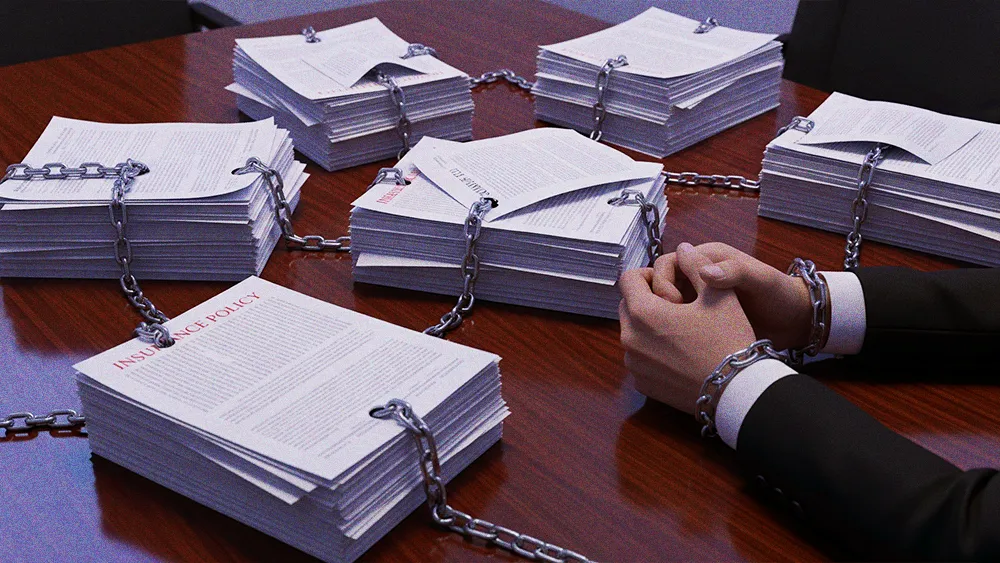

Personal liability for security incidents is no longer theoretical for CISOs. When a breach occurs, accountability isn’t determined by org charts or job descriptions, but by the language buried deep inside insurance policies. That fine print often decides who carries the risk, exposing a hard truth many leaders miss until it’s too late: risk doesn’t disappear when it’s delegated. It follows the title.

Kurtis Suhs is the Founder and CEO of Concierge Cyber and one of the earliest architects of the cyber insurance market, having launched the first cyber insurance product in 1997. He previously served as an investigator with the FDIC and later led cyber and technology risk underwriting at major insurers, giving him a rare perspective on how liability actually unfolds when corporate protections break down.

"When you look at the insurance policy, it might define a director or officer as any duly elected or appointed officer, or it could be as broad as any person holding a title that starts with 'Chief,'" Suhs says. But navigating this reality requires, first and foremost, a deep understanding of insurance policy language.

Know your limits: While strategic insights are valuable, their implementation demands specialized expertise. "I'll add the caveat that unless you're a licensed insurance professional or a coverage attorney, you really shouldn't be giving advice," he continues. "You should let the risk management professionals or attorneys look at coverage. Cyber policies can be 50 to 100 pages long. You have to look at the policy and all its endorsements."

Read the fine print: The primary mechanism of this risk comes from a clause Suhs calls the "knowledge exclusion," a stipulation common in cyber liability insurance and other professional policies. "If an insured has knowledge of any claim or any event or incident that can give rise to a claim, coverage is excluded," he explains. It can void coverage if anyone in the company was aware of a vulnerability that later led to a claim.

Isolating the risk: One of the primary defenses is a clause known as "partial severability." As trends in D&O liability change, this fine print carries significant weight. "With partial severability, where knowledge is limited to a few people like the CEO, CFO, CISO, and general counsel, the knowledge exclusion doesn't apply if the CISO didn't know about it. So if a low-level employee saw something, the knowledge provision is not going to knock that claim out."

To show where insurance simply cannot step in, Suhs points to his time as an FDIC regulator. In banking enforcement actions, regulators pursue directors and officers personally, not just the institution. By law, D&O insurance cannot cover those penalties. "When I was with the FDIC, we went straight to their personal checking accounts to confirm the money was coming from them," Suhs says. In those cases, there is no corporate shield and no insurance backstop.

The three-legged stool: True risk management, and insurability itself, come from a holistic view of the organization, Suhs continues. "It really gets back to the basic three-legged stool: people, process, and technology. The people component is the security awareness training for employees. The process component covers everything from operational policies to business continuity and disaster recovery. And then you have the technology component." Process failures, particularly in the supply chain, can represent a major exposure, turning a trusted supply chain partner into a security blind spot. It's a reminder of the principle that a company’s defenses are only as strong as its weakest vendor, a primary vector for supply chain attacks.

Keep a record: Vendor risk follows the same rules everywhere, but the leverage to manage it changes with company size, Suhs says. Large enterprises can impose security requirements on vendors but must oversee a sprawling third-party ecosystem, while smaller organizations often lack the power to renegotiate contracts and instead depend on brokers to verify that partners actually carry adequate insurance. "The CISO or CTO needs to be part of the insurance conversation," Suhs says. "If you make decisions, have the meetings and document them, because that record is your best safeguard. It won’t stop a lawsuit, but it shows a reasonable process when it matters most."

In the end, Suhs points to a defense that still holds when insurance falls away. "Document, document, document," he concludes. "When a case reaches discovery, the first thing I’m pulling is the board minutes and the committee minutes." Clear records of who met, what risks were discussed, and why decisions were made won’t prevent a lawsuit, but they can be the difference between personal exposure and a defensible record of reasonable leadership.